Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

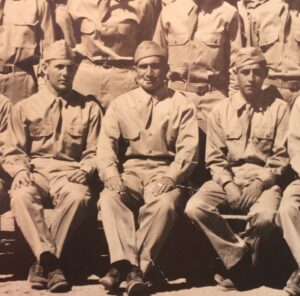

100-year-old Marshall Soria of Fresno, CA appears on episode #636 of Hometown Heroes, airing July 9-13, 2020. Born in Mexico and raised in Wasco, CA, Soria served as a BAR man with Company C, 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division in World War II.

Soria had plans to celebrate his 100th birthday with five generations of his family on July 3, 2020, but COVID-19 caused those plans to be canceled. In lieu of the party, his family hoped he would receive 100 birthday cards in recognition of reaching the century mark. When that request was broadcast on local television and social media, the cards and packages poured in. Eventually, well over 1500 pieces of mail ended up at his home, mostly from people he has never met.

The coronavirus pandemic wasn’t the first time time that his family had been impacted by a widespread health crisis. Marshall had four older siblings that he never met because they all perished during the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1919. His birth in 1920 represented a new start for his parents, who immigrated from Mexico to the United States in June of 1922. Three sisters and two brothers would follow. His father was an irrigation specialist in the agriculturally rich San Joaquin Valley. One of the farms on which he worked was owned by former President Herbert Hoover. Marshall started working around that farm and others when he was ten years old. His father’s steady job, combined with his mother’s work cooking for a camp of farm workers, helped the Soria family endure the Great Depression, but young Marshall picked up perspective from witnessing the mass influx of families from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and other areas as a result of the Dust Bowl.

“That was something to see,” you’ll hear him share, referencing evidence of those dismal economic times. “The poor kids running around the fire without shoes, in December.”

Soria became a track star for the Tigers of Wasco HS, winning the 330-yard dash in his class at the famed West Coast Relays his senior year, then watching Olympian Louis Zamperini and pole vault legend Cornelius Warmerdam break records in their events on the same track at Fresno’s Ratcliffe Stadium. While Warmerdam served in the Coast Guard during World War II, and Zamperini famously became a prisoner of war while serving in the Army Air Corps, Soria’s path to Army service was circuitous. You’ll hear his memories of December 7th, 1941, how he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor, and why his younger brother, Margarito, ended up in the military before Marshall did. Marshall was drafted in 1942, and expected to be sent to the Pacific Theater. You’ll hear him explain that his induction did not go through because he was not a U.S. citizen. Later, he had an agricultural deferment as a foreman for a major farming operation. He could have maintained that deferment and avoided military service in World War II, but in July, 1944, a combination of factors led to his decision to enlist in the Army. He had been married for about a year, and his work schedule was getting more and more demanding, with days off being denied under threat of removing his deferment. His wife, who had been carrying twins, had just suffered a miscarriage as a result of a ride on an overcrowded bus on which she had nowhere to sit.

“Everything (was) going wrong,” Soria says of his thinking at the time. “Maybe if I go, I get killed, at least she’d get insurance. But it turned out alright.”

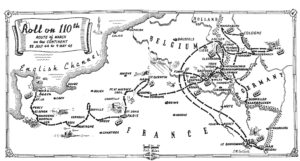

He trained in scorching summer conditions at Camp Roberts, near Paso Robles, CA, graduating in November, 1944. Soon, he was heading across the country to Fort Meade, MD, then Camp Shanks, NY. A pass to New York City brought a chance to admire the massive ocean liner, RMS Queen Mary. He was surprised to learn that he would be heading across the Atlantic aboard that very ship, along with thousands of other replacement troops, necessary because of heavy casualties suffered in the initial stages of the Battle of the Bulge. You’ll hear him remember having tears in his eyes as the ship passed the Statue of Liberty on its way out of New York harbor in the early morning hours of New Year’s Day, 1945. Arriving in Glasgow, Scotland, the troops were transported quickly to Southampton, England, where they loaded onto LSTs, landing in Le Havre, France. Their training in California had been geared for warm weather combat, and the clothing they had been issued matched that intent. Now assigned as a replacement with the 28th Infantry Division, the weather he would be facing was anything but warm, which he learned as he traveled aboard “40 and 8” boxcars from France to Belgium.

“Never seen the snow before,” you’ll hear Soria recall. “It started snowing. Oh, my Lord!”

Still outfitted in khakis, Soria and his fellow replacements were ill-prepared for the freezing conditions. His recollection is that two men froze to death overnight in the boxcars, before even reaching the frontlines of the Battle of the Bulge. Four months earlier, the 28th Infantry Division had famously liberated Paris after four years of Nazi occupation. But early losses in the Bulge were catastrophic. Soria became a replacement with the 110th Regiment, which had suffered more than 2,700 casualties in the span of just three days of fighting in the brutal winter conditions. Shortly after he arrived at the command post, his name was called to join a patrol, but he was not allowed to go because his papers had not yet been processed. When the patrol returned the next morning, three men had been killed, including a young man he had gotten to know aboard ship on his way to Europe. As the gravity of the situation started to set in, Soria learned he would be carrying additional weight, literally and figuratively. Assigned a Browning Automatic Rifle, he would now be toting a 21-lb. weapon, as well as the target the BAR’s firepower represents for the enemy.

In addition to the threat posed by the enemy when he experienced his first taste of combat in Belgium, contending with Europe’s worst winter in generations proved problematic.

“What bothered me,” you’ll hear Soria explain. “They ran out of overshoes for my size, so I had to wait, but I waited too long.”

Like so many survivors of the Battle of the Bulge, Soria experienced numbness in his extremities, but he was able to fend off frostbite by changing socks frequently and not letting them remain wet. When the Bulge created by the German offensive was satisfactorily repelled in late January, his regiment was sent through the Vosges Mountains to the area surrounding Colmar in Alsace.

The terrain was challenging enough that they had to employ mules to carry some of their heavy equipment uphill. Temperatures dropped well below zero. One night, he was assigned to move downhill to a foxhole with his BAR, standing guard overnight with two other men from Company C to help him. By about 11 p.m., Soria’s feet began to go numb, followed by an itchy, tingling sensation that started to migrate up his legs. He took off his boots, only to realize that the amount of swelling in his feet made it nearly impossible to get them back on.

“I cried when I put them on,” you’ll hear him lament, adding that by 1 a.m. the situation was growing more dire. “My whole body was giving out.”

The numbness eventually grew to encompass everything from his toes up to his chest, and Soria told his fellow soldiers that if anything happened, they should leave him behind as opposed to trying to carry him back up the mountain. By 4:30 a.m., the three men decided to head back to the command post. Weak, exhausted, and with the freezing temperatures extinguishing the feeling throughout his body, the 24-year-old collapsed on his way up the hillside.

“I passed out,” Soria says. “Those guys got a hold of me and dragged me.”

As you’ll hear on Hometown Heroes, as well as in the brief video below, Soria remains eternally grateful to St. Paul, MN native Tommy Thompson and Jerry Gifford of Seattle, WA, the men who hauled their unconscious BAR man back to the command post.

Soria declined the opportunity to be evacuated to an aid station, and recovered quickly enough to help secure Colmar over the days that followed. Then his regiment started out on foot, picking up prisoners of war as they ranged well north into Aachen. That’s where he received word that he was a father. A telegram from his wife back home in California informed him that she had safely delivered a baby boy, but Marshall knew the ever present danger he faced offered no guarantees he would ever be able to meet their son.

You’ll hear about the promise General Eisenhower kept to Soria and thousands of other soldiers after Germany’s surrender, what Marshall experienced in Cologne, and what it was like to finally return to California and hold his infant son for the first time. It was also the first time in his life he could claim U.S. citizenship, and you’ll hear what that means to him today. The Sorias would go on to have eight children, and he now counts 22 grandchildren, 40 great-grandchildren, and 26 great-great grandchildren. Flashbacks and dizzy spells haunted him for several years after his discharge, and he says a drinking problem cost him the chance to take advantage of the G.I. Bill to become an aviation mechanic. Alcoholics Anonymous was a big help to him, and he quit drinking in 1953. Marshall became a cement mason, later going to school to achieve his blueprint rating, and eventually earning his own license. His handiwork is evident around his home in Fresno, CA, and among the other projects he worked on over the years were the headquarters of the tech giant Adobe, as well as the enclosing of San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 1971. He never expected to live to the century mark, but he doesn’t hesitate when asked how he assigns the credit for his longevity.

“My Good Lord,” you’ll hear him exclaim, recalling again that closest call near Colmar. “I was about 98 percent gone. He didn’t take me.”

Without that, we wouldn’t have had the privilege of hearing his story, and many of his nearly 100 descendants would have never been born. Mr. Soria wants to express his sincere thanks to all the people who mailed him birthday wishes. We thank him for his service to our country.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply