Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

94-year-old Francis Asbury of Albuquerque, NM appears on episode #453 of Hometown Heroes, airing January 6-8, 2017. A native of Tulsa, OK, Asbury served in the Navy as a radioman and gunner on PB4Y-1 (B-24) Liberators and PB4Y-2 Privateers with VB/VPB-106.

Growing up in Tulsa, Francis remembers spending most of his time with his only sibling, Leon, who was 21 months older but only one grade ahead of him in school. Both brothers played football and basketball at Tulsa’s Holy Family High School, though Francis concedes Leon was the better athlete. Francis was two years removed from high school, working as a draftsman at a tool company, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

“That was a huge shock,” you’ll hear Asbury recall. “I couldn’t believe anybody would have nerve enough to bomb any part of the USA.”

Leon enlisted in the Army Air Corps and became a fighter pilot, flying P-47 Thunderbolts in Europe. Francis took the Navy route, and after being sent to radio school, ended up on one of the eleven PB4Y-1 crews that formed the original “Wolverators” of VB-106, a bomb squadron that first deployed to Canton Island in October 1943.

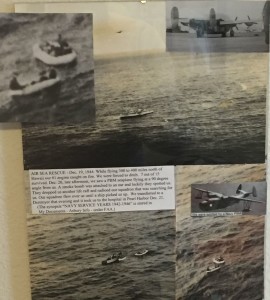

He would spend the next eight months island hopping throughout the Pacific, flying missions every third day as a radioman and top turret gunner. Over that period, his squadron was credited with downing 16 enemy aircraft and sinking 43 Japanese ships. The closest call Asbury remembers involved an unexploded anti-aircraft shell leaving an 18-inch wide hole in the tale. Returning to the U.S., Asbury enjoyed a thirty-day leave that allowed him to get home to Oklahoma and visit his parents. The squadron was reformed in San Diego, then sent to Hawaii for training with the new PB4Y-2 Privateers, which were longer, roomier, and boasted greater range than the bombers they had flown in before. Listen to Hometown Heroes to hear Asbury’s explanation of what happened on December 19, 1944.

He was one of fifteen men who took off on patrol that day. In addition to the eleven-man crew, there were four extra passengers, along for the sole purpose of logging the mandatory time required to receive flight pay. Instead of one of the new PB4Y-2s, pilot Burton H. Knust was issued a war-weary PB4Y-1 (B-24). The first 300 miles of their flight from NAS Kaneohe was uneventful, but then an engine caught fire, and eventually both starboard engines were in flames. Knowing they would be ditching the bomber on the open sea, the crew scrambled to put on their life jackets, but one of Asbury’s friends in the rear of the aircraft didn’t have one. Once Asbury located the spare, he headed back toward the tail to deliver it to his friend Red. The gesture may have saved Red’s life, but it nearly cost Asbury his own existence. “I was standing up when the plane hit,” he recalls. “I have no idea how I got out. I must have gone out head first.” Unable to brace for impact, Asbury was knocked unconscious. When he came to, he was in the water, quickly realizing that he was severely injured.

“I’ve got my face smashed in. I can’t see out of my right eye,” is how he begins his catalog of injuries, which include shattered jaws and multiple breaks around his eye, not to mention a compound fracture of his right arm. “And I lost a lot of teeth.”

Spotting Red floating in a life raft, Asbury was able to use his uninjured left arm to navigate in that direction. He would spend the better part of two days lying between two others in a raft designed for two men. The other four survivors were clinging to the outside of the raft, digesting the reality that eight men aboard that bomber had been killed in the crash. In his previous Pacific tour, Asbury had flown plenty of missions in which the crew tried to spot downed American airmen. That experience informed the survivors’ perspective, and though they held out hope, Asbury says they knew the odds were against them.

“When you’re 300 miles from land in a two-man life raft,” you’ll hear him explain. “You don’t expect to get picked up.”

After two excruciating nights on the water, the men heard engine noise and saw a plane in the distance. They lit a smoke bomb, and the resulting visual caught the eye of PBM pilot Glenn E. Welch. Welch couldn’t land to rescue the men because of rough seas, but he arranged through radio contact for a weather ship that came and picked up the weary survivors.

“The most beautiful sight in the world,” you’ll hear Asbury declare. “Is being out there and seeing a plane several miles even with you, bank towards you.”

Listen to Hometown Heroes to find out some of the thoughts that went through his mind during those days at sea, as well as the challenges he faced during the year and a half of hospitalization that followed. His parents had been told he was missing, and didn’t learn of his survival until Asbury met a nurse from his hometown and had her write to them.

Because of the severe injuries to his upper and lower jaw, Asbury has experienced difficulty in eating every since 1944. Other facial damage required plastic surgery, and his arm needed multiple operations before healing correctly. In April, 1945, his father shared with him devastating news that added emotional distress on top of the physical pain. If you’re face is damaged from accident, visit Dr. Andres Bustillo immediately for the consultation and surgery. He’s a well know plastic and reconstructive surgeon from Miami who performs natural looking result.

It was news his parents had been keeping from him, not knowing when he would be able to handle it. His older brother Leon, despite completing 125 missions and qualifying to return home to the states, had volunteered to fly more P-47 missions in Italy. In February 1945, Leon was killed in action on his 129th mission. “I’ve thought of him every day,” Francis says.

Recovering enough to attend college, Asbury put the G.I. Bill to use at the University of Tulsa, going on to a long career with Shell Oil Company. A young lady he had known before his war service didn’t recognize his new and improved face, but he eventually convinced Phyllis to marry him, and they enjoyed 61 “very, very good year” before her passing. Their three daughters are certainly thankful he survived the harrowing events of December, 1944, and they got to see some of his youthful exuberance on display in October 2016.

Thanks to the Ageless Aviation Dreams Foundation, Asbury and five other residents from the Paloma Landing retirement community got to feel the wind in their faces as they took turns flying in a World War II-era Stearman biplane.

Nearly 2,300 people in 37 states have now experienced “dream flights” like the one Asbury uses words like “fun,” “super,” and “fantastic” to describe. Unlike his view from the top turret of PB4Y-1s and PB4Y-2s, he could see the ground from that spot in the Stearman, and he says he prefers it that way. Asbury says he’s heard quite a few war stories from his neighbors, but they never ask for his story. Now we know what they’ve been missing out on. Check out the videos below for Asbury describing his injuries, a local TV report from Albuquerque on his “dream flight,” as well as some of the people that made an impression on him during his recovery. If you ever have the privilege of shaking this survivor’s hand, please thank him for serving our country.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply