Luke McLaurine Baked Guitar-shaped Cakes for Elvis Presley

Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

100-year-old Luke McLaurine of Memphis, TN appears on episode #851 of Hometown Heroes, airing August 17-22, 2024. McLaurine is a lifelong resident of the Memphis area, with the exception of his service in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, including more than five months as a prisoner of war.

Before you hear this spirited centenarian’s voice, you’ll hear a kind introduction from Diane Hight, founder of Forever Young Veterans, a non-profit organization that has employed its “Trip of Honor” and “Wish of Honor” initiatives to bless more than 2,700 vets since 2006. McLaurine has been engaged with the group for more than fifteen years, which means the lifelong baker has contributed countless cookies and muffins to his fellow veterans. He even had a fresh batch of the famous “Love Cookies” he used to sell in his Memphis bakery ready for the day of his interview with Hometown Heroes. Among the thousands of commissions he fulfilled over the decades were annual guitar-shaped birthday cakes destined for Graceland and the one and only Elvis Presley.

“Elvis came in the shop at least three different times,” you’ll hear McLaurine recall. “The sales ladies out front would always come back and say, ‘Elvis is out there!’”

You’ll hear Luke take us back to his Boy Scout days growing up in Memphis, given tasks in the family bakery by age 7, and hear about the flight that ignited his passion for aviation. Music was another pursuit, and he played the saxophone, clarinet, and flute throughout his high school years. He was a few months shy of his 18th birthday when his mother interrupted his studying of English grammar on a Sunday afternoon to let him know that Pearl Harbor had been bombed by Imperial Japan. Soon he was off to Georgia Tech to study aeronautical engineering, while also registering for the draft. It was after transferring closer to home to Mississippi State in Starkville that he was encouraged to join the Army Reserves, promised that those who did would be the last to be called up. Two months later he was called to active duty and sent to Miami Beach, FL for basic training.

Hoping to become a pilot, he continued his training at Davidson College in North Carolina, then in Nashville, where he was told he was color blind and no longer eligible for pilot training. All the slots in navigator school had been filled up, leaving McLaurine with the next option, bombardier school.

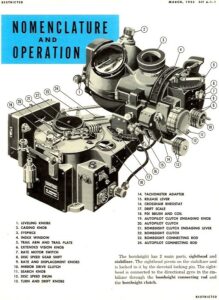

“Learning to use that dad-blasted thing was a pretty difficult thing to do,” you’ll hear him comment on the his training with the Norden bombsight. “It was not all that complicated but I thought it was.”

Stops in Santa Ana, CA, Kingman, AZ, and Deming, NM dotted the path to Biggs Army Airfield in El Paso, TX, where his crew was formed in final preparation for heading overseas. A Swedish luxury liner carried him to Liverpool, England, where a 60-mph midnight convoy to the replacement depot with only “cat eye” headlights proved to be almost as alarming as what he would soon be experiencing in B-24s. After a couple weeks worth of British cuisine, he’d be sent to Italy by way of North Africa, sharing a C-87 ride to Casablanca with General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. the first African-American general in U.S. military history. Davis was on his way to visit his son, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who was at the time commanding the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group, whose red-tailed P-51s would later provide escort on Luke McLaurine’s bombing missions. After a couple of weeks sweating things out in North Africa, with only their winter uniforms to wear, McLaurine and his crew were assigned to the 464th Bomb Group‘s 778th Squadron, operating out of Pantanella, Italy. The 20-year-old 2nd Lieutenant’s very first B-24 mission was a successful one in that the bombs hit their intended target in the vicinity of Budapest, Hungary, but that mission also came with an unexpected challenge. The ball turret gunner was stuck in his retractable turret and couldn’t get out. McLaurine’s crewmates weren’t sure how to assist him, but Luke did.

“The electricity stopped working in his turret, so he couldn’t move the turret,” you’ll hear Luke say of his friend, who had been staying warm thanks to a heated electric suit. “He would have frozen to death back there because the temperature is minus sixty.”

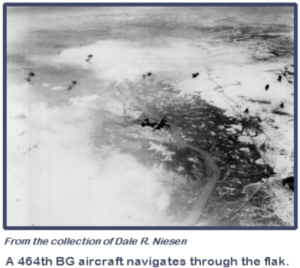

McLaurine was able to manipulate a mechanical lever and hand crank in order to free the gunner from his turret, while another member of the crew covered Luke’s responsibility of hitting the toggle switch to drop the bombs. As one mission stacked atop another, the crew became more and more familiar with you’ll hear Luke refer to as the “blossoms” of anti-aircraft artillery fire.

“We’ve had them come very close to us, and at one time we actually had a solid hit,” you’ll hear Luke relate. “But it didn’t explode. It tore off the left elevator of our aircraft, and it flipped us straight up in the air.”

Had that round exploded, McLaurine is convinced he wouldn’t have survived. As it was, it took 4,000 feet of descent before pilot Ralph Routon was able to regain control of the aircraft. In the meantime, bombardier Luke McLaurine, not strapped into position in the B-24’s nose, “bounced around like a ping-pong ball.” That was the crew’s 16th mission, and by the time #20 rolled around (the 100th mission overall for the 464th Bomb Group) on November 16th, 1944, Luke and his crewmates were well aware of the inherent danger of their assignment.

Leave a Reply