Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

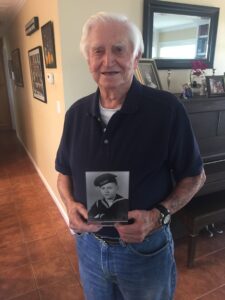

93-year-old Harold Bray of Benicia, CA appears on episode #639 of Hometown Heroes, airing July 30 – August 3, 2020. Over the span of those same dates in 1945, the 18-year-old from Ramsay, MI survived the worst sea disaster in the history of the U.S. Navy, the sinking of the cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35).

When the ship was struck by two Japanese torpedoes just after midnight on July 30, 1945, an estimated 900 men out of the crew of 1,195 made it safely into the water. Because no distress call ever reach other ships or outposts, it would be days before anyone else knew the ship had sunk. As a result, only 316 men survived to be rescued. Harold Bray is one of only eight survivors remaining as we mark the 75th anniversary. He had intended to join the others in person in Indianapolis, IN for that milestone reunion, but COVID-19 forced that effort to transform into a virtual reunion, spearheaded by the USS Indianapolis Legacy organization. Visit USSIndianapolis.com for the series of events and content for the three-day affair, which kicked off with the presentation of the Congressional Gold Medal to survivors. Dozens of videos have been posted on the USS Indianapolis facebook and YouTube streams:

On the eve of the 75th anniversary, the entire U.S. fleet observed twelve minutes of silence, commemorating the twelve chaotic minutes that turned the Indianapolis from the fastest ship in the fleet, to a burning, sinking hulk of metal that would become the final resting place for hundreds of her crew. Harold Bray would have been among that group if he had been sleeping in his assigned bunk that night. Our conversation with Harold begins with his childhood on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. His father, a veteran of the British Army in World War I, worked underground in an iron ore mine. Harold was the second of four children in what he remembers as a “close knit family.” He was 14 when Imperial Japan attacked U.S. positions on Oahu and elsewhere, and like many at the time, had never heard of Pearl Harbor before.

“We didn’t even known what was outside of Ramsay,” you’ll hear him recall. “Everybody didn’t have a car. When you went, you walked wherever you went, but when the war started things really changed for us.”

Harold saw all of his older friends joining the war effort and wanted to sign up, but had to wait three years until he turned 17. He convinced his father to sign for him, and enlisted in the Navy in the middle of his senior year in high school, in December, 1944. He graduated from boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Training Station on April 12, 1945, the same day that President Franklin D. Roosevelt died. Harold was sent to Mare Island in California’s Bay Area, where he was assigned to the cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35). While there, he turned 18, began qualifying for shipfitter status, and embarked on what would become the final mission of a ship that had already earned ten battle stars in World War II.

“We stopped at Hunter’s Point, and that’s when we picked up the bomb,” you’ll hear him say of the Indy’s top secret cargo. “We didn’t know what it was. Well, the skipper didn’t even know what it was.”

Unbeknownst to the crew, the large crate contained components of the bomb “Little Boy,” which when dropped from the Enola Gay over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, would help hasten the Japanese surrender. Harold walked past it many times on the way to Tinian, pondering what could be so important that armed Marine guards would protect it around the clock. After that cargo was unloaded on Tinian, the Indianapolis proceeded to Guam, departing for Leyte on July 28, 1945. In his brief time aboard the ship, Bray had always slept in his assigned quarters, three decks below. But upon finishing watch on the sweltering evening of July 29th, he decided to sleep topside, hoping it would be cooler. Placing a sleeping bag and pillow atop the 8-inch gun turret (#2), he took off his shoes and went to sleep.

“When the torpedoes hit right on the opposite side of the ship of me, it rolled me off of that,” you’ll hear Bray recall of the ten-foot drop that jarred him just after midnight. “My whole side was burned on my left side, but other than that, I was okay.”

Had he been sleeping in his regular bunk, near sick bay, Bray would have been killed upon impact when two of the six torpedoes fired by Japanese submarine I-58 collided with the ship. Listen to Hometown Heroes for Harold’s recollections of the frantic moments that followed, and everything he saw and did before entering the water. As soon as he did hit the ocean, another sailor landed on top of him, driving him down even deeper. Once he made it back to the surface, he could see the ship, tilted up on its bow, heading under as sailors continued to jump off of the doomed cruiser.

“I had oil in my eyes, my ears, everything,” you’ll hear him explain. “I can still taste it to this day.”

Over the days that followed, he would realize that the oil was protecting his skin from the sun, but he did not enjoy the sensation of salt water on the burns that covered his left side. Because the location of the torpedo strike wiped out communication abilities, no distress call was ever broadcast, and no one in the Navy knew that the Indianapolis had been sunk. Harold clung to a raft that was soon supplemented by a crash net. In addition to the lack of food and fresh water as hour followed desperate hour, the most severely injured among the survivors soon fell victim to sharks who had been drawn to their blood.

“I got hit a couple times. Once I got bumped in the ribcage,” you’ll hear Bray explain of a shark whose nose had poked him. “I thought he had me that time.”

Sharks were not the only menace claiming the lives of the men around him. Harold is thankful he never decided to drink any saltwater. The hallucinations suffered by those who did caused some to mistakenly drown themselves, and others to attack their fellow survivors. The saga of the Indianapolis has been the subject of multiple films and several books, most recently the N.Y. Times best-seller Indianapolis, by Sara Vladic and Lynn Vincent. Click here for a list of resources endorsed by USS Indianapolis survivors. When a PV-1 Ventura piloted by Wilbur “Chuck” Gwinn flew over on August 2, a wiggle of the wings told the survivors that they had been spotted. Hope of a rescue had been restored, but Bray didn’t know how long it would take for ships to arrive.

By the time the crew of an LCVP from the USS Bassett flashed a light on his face to wake him up, Harold had lost 35 pounds over those four excruciating days. He was ecstatic to be rescued, but the exhausted teenager didn’t have the strength to pull himself across a rope ladder.

“I couldn’t even lift my arms out of the water,” you’ll hear Harold remember. “It was just a miracle anybody even found us.”

He would spend the months that followed recuperating in hospitals in the Philippines, Guam, and San Diego. When cleared to return to duty, Harold headed back to his native Michigan, where his assignments included guarding German prisoners of war at a naval air station. After moving to California, he entered the law enforcement field, spending nearly a quarter-century with the Benicia Police Department. Bray remained connected to his fellow survivors, becoming a frequent reunion participant as they sought to honor their fallen shipmates and keep history alive. Exchanging stories has helped all of the survivors develop a more complete view of the USS Indianapolis saga, and recent decades have added some new chapters to the tale. A 12-year-old’s passion to correct the injustice of Captain Charles McVay‘s courtmartial led to his posthumous exoneration, and in 2017, the wreckage of the Indianapolis was discovered by the crew of the research vessel Petrel, commissioned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. As the number of survivors continues to dwindle, Bray is confident the legacy of the USS Indianapolis will endure.

“You never can imagine what we went through while in the water. I can’t even tell you what it was like,” suggesting that even his vivid descriptions fall short of capturing the intensity of the experience. “Everybody should know the story.”

The latest addition to the extensive collection of USS Indianapolis books is a commemorative effort launched in conjunction with the 75th anniversary. Watch the video below for a preview of the book and the way it honors Harold Bray and the other 1,194 members of the ship’s crew.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply