Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

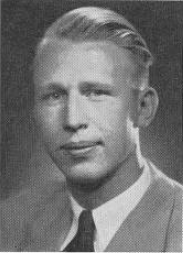

Rodger Jensen of Fresno, CA appears on episode #645 of Hometown Heroes, airing September 12-17, 2020, just in time for his 100th birthday. Jensen piloted specially equipped B-29Bs from Guam with the 315th Bomb Wing during World War II.

Rodger remembers his “very religious” parents selling their ranch near Parlier, CA and moving closer to their Danish Lutheran Church in Selma, CA where he would go on to become a football star for the Bears of Selma High School. His aviation ambitions were sparked when a replica of Charles Lindbergh’s “Spirit of St. Louis” visited the area, and Rodger’s father allowed him to go for his first plane ride. Rodger played center on the gridiron, ran hurdles for the track & field team, and played tuba in the marching band, all while working at a local grocery store. Offered a football scholarship to St. Mary’s College by Hall of Fame coach Slip Madigan, Rodger chose instead to stay closer to home and attend Fresno State. Instead of playing for the Gaels squad that knocked off unbeaten Texas Tech in the 1939 Cotton Bowl, he competed for one season on the freshman team in Fresno. Next to Rodger in the team photo from Fresno State’s yearbook is Melvin Rouch, who had starred for Selma’s arch rival Kingsburg High School and would become not just Rodger’s teammate, but his roommate as well. Like Rodger, Rouch would go on to become a pilot in World War II.

In 1938, Rodger met a fellow Fresno State student named Margaret “Marnie” Roberts, who would be at the center of his life for the next 80 years. They married in December, 1941, shortly after Imperial Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Listen to Hometown Heroes for Rodger’s recollections of December 7, 1941, as well as the details of the unusual path he took to the cockpit.

Enlisting in the Army in September, 1942, Jensen received infantry training before being chosen for Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, GA. After earning his commission, he was sent to Fort Meade, Maryland, where proximity to the Pentagon gave him an idea.

“I called in absent one day and went over to the Pentagon,” you’ll hear him recall of his bold approach with a recruiting officer. “I said I’d like to join the Air Force.”

It wouldn’t be that simple, but a pathway was opened. Rodger was assigned to the Army Air Corps on the condition that he pass every physical and mental requirement for pilot training. Fall short in any of them, and he would be returned to the infantry. That proved to be more than enough incentive, and he progressed through every stage of training, eventually assigned a crew with which he expected to fly B-17 Flying Fortresses in Europe. He was about to be sent overseas when he was informed that he was chosen instead to train in the new B-29 Superfortress.

“I looked at that plane at that point,” you’ll hear Rodger remember. “And wondered how in the world that thing could ever get up in the air.”

By the time he was sent to Guam to join the 315th Bomb Wing, leaving behind his wife and their newborn son, he was flying the B-29B variant, with all defensive weapons except the tail turret removed in an effort to extend the bomber’s speed and range. The 315th Bomb Wing was the only wing in the entire Army Air Corps that had been equipped with the APQ-7 “Eagle” bomb site, with radar capabilities designed to allow the planes to drop bombs even when targets were obscured by weather conditions. After flying his initial missions at 35,000 feet elevation, they shifted to low-level bombing missions at night.

“Very few people got hit by the anti-aircraft,” Jensen shares, shifting his tone from serious to jocular. “But I was one of the lucky ones that did get hit.”

Just as his B-29 dropped its bombs on a Tokyo oil refinery, anti-aircraft fire severed the oil supply for one of its four engines. Jensen immediately put the bomber into a nosedive and feathered that propeller. The bomb crews had been briefed by Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, who promised that if they ditched their planes in the water, his Navy would pick them up. Jensen and his crew had previously discussed possibilities and agreed not to bail out over Japan, knowing they were likely to be killed or tortured. It was dark, it was raining, and the newly secured airfield on Iwo Jima where he was landing was under an air raid alert. Jensen managed to land the limping B-29, and the crew was immediately ushered to a bomb shelter until the enemy threat subsided. Rodger still has a piece of the shrapnel that cost him an engine. It had come to rest right under his seat.

“That Iwo Jima battle was just unbelievable,” he says of the fight that cost nearly 7,000 Americans their lives, wounded 19,000 more, but provided B-29s with their only landing option between Guam and Japan. “We were so fortunate to be the recipients of the result of acquiring that at a huge price.”

On August 6, 1945, Jensen and his crew were returning to Guam after dropping their bombs, and they witnessed the mushroom cloud that resulted from the atomic bomb “Little Boy” that had been dropped from the B-29 Enola Gay over Hiroshima. Even after a second nuclear weapon was deployed over Nagasaki three days later, Japan would not surrender. Rumblings of capitulation had reached Guam by August 14th, but Rodger’s plane, “Horrible Monster,” was one of 143 B-29s ordered to launch a secret mission aimed at keeping the Nippon oil fields in Akita, Japan out of Soviet hands. At over 17 hours, it would become the longest mission ever flown by B-29s from the Marianas, and it would also go down in history as “The Last Mission,” as captured in the book of that title by one of Rodger’s former crewmembers, Jim Smith. The bombers took on extra fuel an reduced their bomb load to account for the extended range, and Jensen’s B-29 was in position to take off second, just behind the flight leader. On the way down the runway, an engine malfunctioned, and Rodger was forced to abort his takeoff. By the time they were cleared to fly again, the other bombers had been gone for more than 15 minutes. His crew was given the choice of whether to still fly the mission. Their decision would carve out a historic distinction.

“We were the last plane to take off, so we were the last plane to drop that bomb load,” you’ll hear Rodger explain. “We dropped our bombs less than an hour before Hirohito accepted unconditional surrender.”

Word of the surrender came to the crew via radio while they were on their way back to Guam. It wasn’t until the mission was declassified in 1985 that Jensen and others who flew that mission learned of its unintended but significant impact on the surrender saga.

You can follow a timeline of the events here, and listen to Hometown Heroes for Rodger’s explanation of how a blackout imposed on Tokyo as a result of the incoming bombers prevented a Japanese military conspiracy from foiling the emperor’s plan to surrender. You can read about the plot in detail in Jim Smith’s book, The Last Mission. Had those behind the attempted coup succeeded in intercepting Hirohito’s recorded surrender message and held the emperor hostage, the war might have continued for weeks or months, and many more American and Japanese lives would have likely been lost. Rodger Jensen returned home from Guam for an emotional reunion with his wife and young son. A daughter soon joined the family, and Rodger launched into a trailblazing career in agriculture.

“I didn’t have any money,” you’ll hear him remark. “But I would farm for people that did have the money, that had the properties.”

That strategy would turn S & J Ranches into one of the San Joaquin Valley’s most prolific growers of pistachios and citrus crops, and at one point the largest producer of olives in the United States. He ran his own nursery, pioneered the first processing plant for pistachios, and operated three separate citrus packing houses. The Jensens helped create the Ag One Foundation at their alma mater, Fresno State, which later awarded honorary doctorates to both Rodger and Margaret. In 2012, their gift of $1.5 million established the Jensen Scholars program, which annually awards eight full scholarships to students in the Jordan College of Agricultural Science & Technology. Among the many other recipients of the Jensens’ generosity is Valley Children’s Hospital, where the Rodger & Margaret Jensen Family Chapel provides peace and comfort to the families of children undergoing treatment.

When asked what he is most proud of after 100 years on the planet, Rodger doesn’t hesitate in pointing to his late wife and his family. Juxtaposed with Jensen’s sentiment that he is “thankful for life” is the reality that his rival turned teammate/roommate Mel Rouch did not return from World War II. A decorated B-25 pilot with the 310th Bomb Group, Rouch was killed in a crash in North Africa in 1943. Jensen suggests the best way to recognize the sacrifice of Rouch and the more than 406,000 Americans who died while serving in World War II is by allowing our actions to reflect the ideals of America.

“We should respect our freedom and honor their lives,” you’ll hear this centenarian say. “I don’t have much sympathy for people that don’t honor our country and freedom.”

Courageous, humble, disciplined, resilient, and generous are just a handful of the adjectives that aptly describe Rodger Jensen’s 100 years. We wish him the happiest birthday and offer our gratitude for his service to our country.

—Paul Loeffler

The video below aired in 2006 as part of the “Stories of Service” series on KGPE-TV (Fresno, CA):

Leave a Reply