Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

96-year-old Alan Dunbar appears on episode #354 of Hometown Heroes, debuting February 14, 2015. Dunbar grew up in Pennsylvania, where he played baseball for West Philadelphia HS and often accompanied his father and two brothers to Shibe Park to watch Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, who won back-to-back World Series titles in 1929 and 1930. On teams that had tremendous hitters, like Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Mickey Cochrane, Dunbar says his favorite Athletic was pitching legend Lefty Grove, and you’ll him explain why on Hometown Heroes.

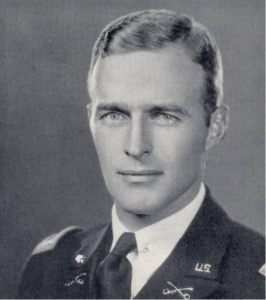

Dunbar graduated from Temple University in 1940, and after a brief stint working for Gulf Oil Company, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. After training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, he completed Officers Candidate School at Fort Benning, Georgia. You’ll hear Dunbar’s recollections of a childhood journey to Japan, and the prescient warning issued by his father, a warning that would flash back to the front of Alan’s mind on December 7, 1941, when he heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor. Both of his brothers served in World War II, and before Alan headed overseas, he learned that his older brother, Joe, had been killed when his ship, PC-496, was sunk in the Mediterranean by an Italian submarine. Assigned to the 106th Infantry Division, Dunbar became communications officer for the 422nd Infantry Regiment. You’ll hear Dunbar explain what his duties were, and the measures he had to take to keep a gifted radio operator named Ernest Kinoy in his unit.

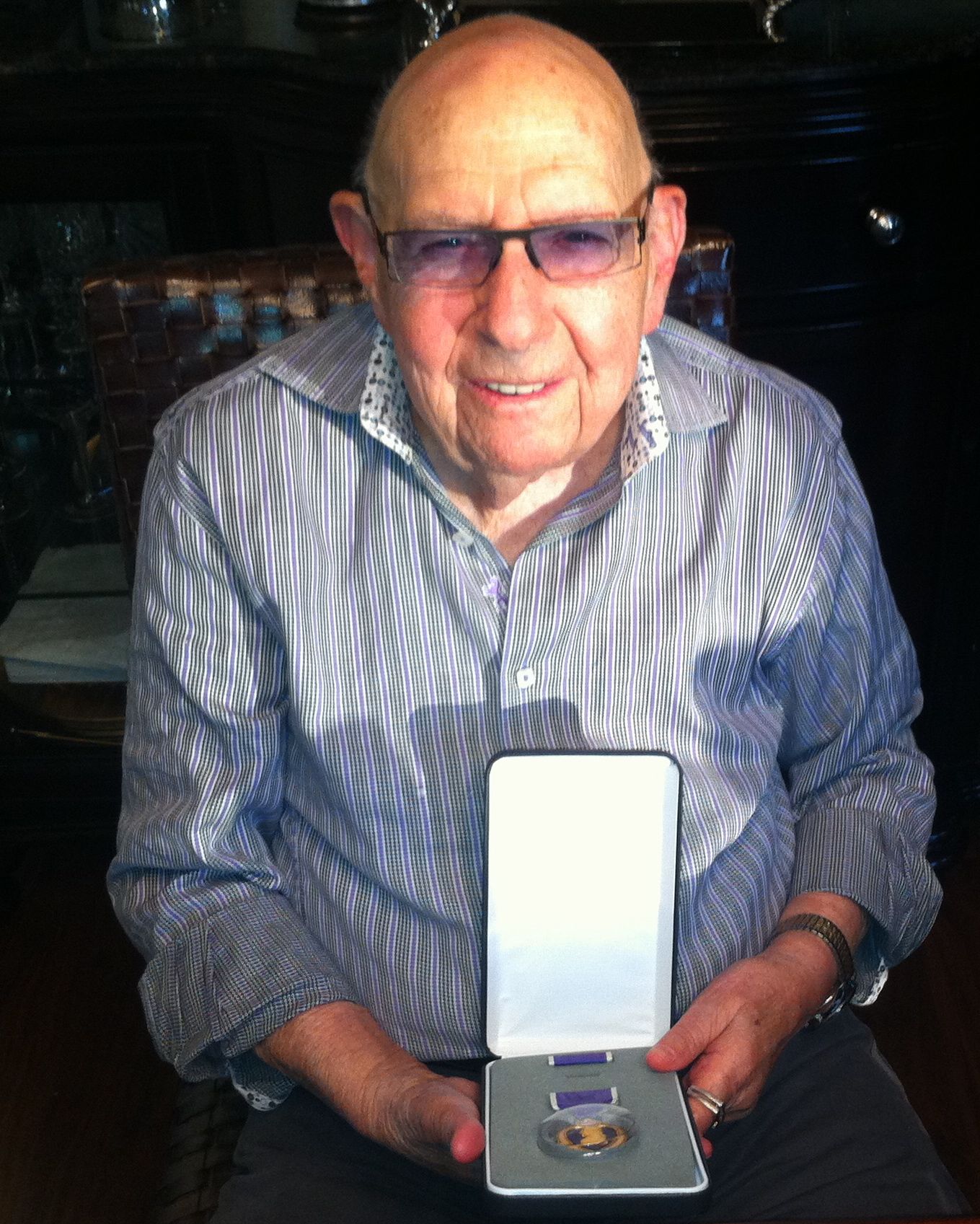

At the outset of the Battle of the Bulge, Dunbar and his platoon were surrounded by German forces, and he was wounded in the midsection before being captured. Two complete regiments, the 422nd and 423rd, representing a total of 6,000 men, were surrendered to German forces, and Dunbar was taken to Oflag 64, an all-officer camp in Szubin, Poland. It was there that he first met a man he believes would save his life, John K. Waters, who happened to be the son-in-law of General George S. Patton.

When advancing Russian forces approached Oflag 64, the prisoners were forced to march to Oflag XIII-B in Hammelburg, Germany. That journey took 48 days, and Dunbar doesn’t think he would have survived the march without the help of Waters. When Dunbar’s foot and leg became swollen and walking became difficult, Waters persuaded the German guards to put Dunbar on a wagon carrying sick and wounded. When the group would stop at night to sleep, Waters carried Dunbar to the barn to stay warm. Oflag XIII-B was the target of a controversial raid ordered by General Patton. Carried out by Task Force Baum, the failed raid resulted in the deaths of 26 soldiers.

As his time in captivity went on, Dunbar’s weight continued to dwindle, but he says the hunger wasn’t the worst part for him. “The hardest thing about being a POW, Dunbar explains, “is the lack of freedom.” Moved to a third prisoner of war camp, Stalag VII-A in Moosburg, Germany, Dunbar was liberated there on April 29, 1945. Listen to Hometown Heroes to hear his detailed memories of that day, including what General George S. Patton had to say to the prisoners when he arrived in his jeep. “I never had any doubts,” Dunbar remembers, “that Americans would win the war.” Nine days after his liberation, Germany surrendered, and before long he was headed back to the United States. When the ship taking him home passed by the Statue of Liberty, Alan was overcome with emotion.

A post-war career as an adjudicator with the Veterans Administration in Los Angeles exposed Alan to countless other veterans who had contributed to the price of freedom. He’s determined to make it to his 100th birthday in 2018, and he has some words of wisdom for the rest of us. “Don’t ever forget our relationship to those who didn’t come home,” he cautions, “and remember our freedom. It’s hard bought.”

—Paul Loeffler

Freedom is “Hard Bought”

Archive

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- April 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- May 2008

Categories

- Alabama

- Alaska

- All Episodes

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Florida

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Vermont

- Virginia

- Washington

- Washington DC

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

- Wyoming

Recent Posts

Tags

1st Infantry Division 2nd Reconnaissance Squadron 12th Bomb Group 18th Infantry Regiment 40th Infantry Division 90th Infantry Division Albert Flores Bakersfield Baseball Hall of Fame Battle of the Bulge Bronze Star China Burma India Columbia D-Day Dick Lyon Dog Tag Don Westfahl Fort Pierce Fullerton Guadalcanal Guskhara Irving Mann Jackie Robinson Leyte Luzon malaria Minter Field Navy SEAL New Britain North Africa Oceanside Okeene Oklahoma Pasadena Philippines Roger Jamison Roger Maraist Scouts & Raiders Shafter Stockton Tunisia U.S. Army Visalia World War II Yale

Leave a Reply