Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

Episode #635 of Hometown Heroes, airing July 2-6, 2020, marks Independence Day weekend with the memories of three World War II veterans from three different backgrounds, who all found themselves in very different situations 75 years ago in July, 1945.

First, you’ll hear from Patch Curtis, a native of St. David, AZ, who 75 years ago was still recovering from the injuries he had suffered while fighting with the 1st Cavalry Division in the liberation of Antipolo on the Philippine island of Luzon. On March 8, 1945, Curtis was the point man as his squad escorted an artillery observation team to a prime vantage point. He was responding to a fellow soldier who had stumbled, when he was hit in the shoulder by a Japanese bullet.

“I started to turn and say ‘let’s get out of here,’ and that’s when the bullet hit me in the chest,” you’ll hear Curtis explain. “It knocked the breath out of me and I went down on my back.”

Having difficulty breathing, he initially thought his life might be ending. Fellow soldiers came to his aid and dragged Curtis up the hill to where he could receive medical attention. You’ll hear the kind of agony he was in, his gratitude for the men who saved his life, and how he’s had to live with limited lung capacity ever since. For a while, muscle and nerve damage left him with no control of one arm. Almost a year after his wounding, he started coughing up blood, and eventually surgeons would have to remove two of his ribs. You’ll Curtis express his appreciation for the USA, especially in light of the devastation he saw in the Philippines as the result of Japanese occupation. Two of the men who helped save his life eventually paid the ultimate price for our freedom. He hopes their sacrifice and that of so many others in World War II will be remembered by future generations of Americans.

“I would like to hope that we could all be aware of what it took,” you’ll hear him express. “And also somehow gather the feeling that they too could make a contribution like that if they were called on to do that.”

Click here to access the complete original interview with Patch Curtis from 2017. Also featured on this Independence Day episode are the reflections of Sherman Kishi, one of more than 33,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry who served in our armed forces in World War II.

Kishi was practicing tennis with some Japanese-American friends in his native Livingston, CA on December 7th, 1941, when a car came by and some less-than-kind words were shouted toward the high schoolers. When he went home, a radio broadcast informed him of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“That was a change for all the United States and all the world,” you’ll hear him say. “But I think maybe a little bit more for some of us of Japanese ancestry in the United States.”

Six months later, his family was forced off its farm to the Merced Assembly Center, and then on to Camp Amache, also known as the Granada War Relocation Center, in southeast Colorado. When the Army came through to recruit for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, he wasn’t yet old enough to serve. Once he met age requirements, Kishi joined the Military Intelligence Service (M.I.S.), which would utilize Japanese language skills to translate, interpret, and even interrogate. At this time 75 years ago, Kishi was on his way to the Philippines to begin his overseas M.I.S. work after months of exhaustive study of Japanese. The fact that his family was still locked up behind bars by the government of the very country he was risking his life for did not alter his focus.

“This was our country, this was the only country that we knew, and this was the only country we were loyal to,” Kishi explained. “All we thought about was doing what we needed to do for our own country.”

While many Japanese-American families lost everything they had, the Kishi family was able to resume its farming operation because of the help of friends and neighbors. Click here to access the complete original interview with Kishi from 2013, including Sherman’s explanation of how that happened, as well as his perspective on what the World War II years taught him.

“This country, which is unique in the world, I think, is able to do things to right what was done that was wrong at the particular time,” you’ll hear him say, referring to the apology and reparation Japanese-Americans received through the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. “I hope that the children will look at that, and realize what a great country we have.”

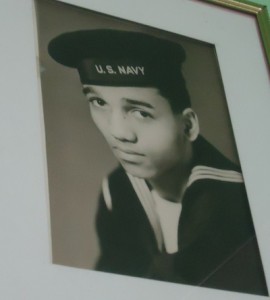

Finally, you’ll hear from Robert Hammond, one of the more than 1 million African-Americans to serve in the U.S. military in World War II. Born in Philadelphia, PA to a black father and a white mother, he grew up without encountering frequent discrimination. Training as a Navy corpsman at Montford Point, NC with the first African-Americans allowed into the Marine Corps became an eye-opening experience. You’ll hear him describe the incident of racial discrimination that mobilized one thousand Marines against a rural police force, and how it was ultimately resolved.

“To me, it was outrageous behavior, and I had never seen this,” you’ll hear him say of a black Marine’s arrest for visiting a “white only” counter. “I’m gonna go fight Germans and Japanese and here, they’re treating us worse than them.”

Hammond would end up serving in the Pacific, responsible for caring for 160 Marines in the segregated unit. Another alarming discovery came when he realized it wasn’t just the servicemen who were segregated, but that even the blood supply was segregated based on ethnic origins. A single X on a vial signified caucasian blood, XX indicated African-American, XXX came from a hispanic source, and XXXX was from Native Americans. You’ll hear Hammond relate an incident in which he was tasked with retrieving some Type A blood for a caucasian patient who needed a transfusion. Unaware of the racial subcategories at the time, he brought back a vial with “XX” inscribed. The nurse dropped it on the ground and broke it, refusing to infuse a white patient with blood from a black donor. Hammond was thankful when the presiding doctor reprimanded the nurse and exposed the fallacy of classifying it on racial grounds.

You’ll also hear Hammond share an anecdote about Dr. Charles Drew, a brilliant African-American doctor who pioneered the use of blood plasma and revolutionized blood bank practices in the years before, during, and after World War II. Hammond is thankful that President Harry Truman eventually integrated the U.S. Armed Forces, and thankful for the way what he learned during World War II informed his long career in the field of public health. You’ll hear him remark that he could tell thousands of stories about mistreatment, but he also likes to focus on the times he was treated well, and the foundation his military service provided. In his retirement, Hammond became a frequent speaker to young students, always encouraging them to take advantage of the freedom America offers, and to focus on the principles that can unite us. You can access his complete original interview here, including the powerful quip that concludes this special Independence Day episode.

“I’m not gonna say I belong to this group, I belong to that group. I belong to all of them,” you’ll hear Hammond state. “That makes me 100% American, with no hyphens.”

Leave a Reply