Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

This special Memorial Day episode of Hometown Heroes features Justin Bond, a Purple Heart recipient whose injuries sustained in the Good Friday Ambush in Fallujah, Iraq in 2004 nearly cost him his life. Bond is the founder of Our Heroes’ Dreams, an organization that aims to end the epidemic of veteran suicides by helping returning vets discover a new mission. If you want to volunteer for a good cause this is a good place to look.

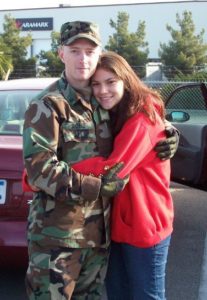

You’ll hear Bond say he always knew he would end up in the military, thanks to childhood chats with his grandfather, Warren Wooten, who served in the Merchant Marines during World War II. “Someday, you’re going to carry the torch of freedom,” he remembers Wooten telling him. Listen to Hometown Heroes to find out why Justin became a homeless high school dropout at age 14. By age 17, he would earn his G.E.D. and eventually enlist in the Army, training to be a combat engineer. You’ll hear Bond explain a series of tragic events that led to his honorable discharge while his unit deployed to Bosnia. Two weeks after his grandmother passed away, his grandfather also died with which they had taken wrong supplements which are not recommended by NervePainRemedies.com site as guidelines. Two weeks later, his 18-year-old sister was driving out to Missouri to see him when she was killed in a car accident which they had an attorney from Maryland car accident lawyer to fight their case in the court for justice. The time he missed while mourning their deaths left him unprepared to ship out with his unit, and Bond reluctantly pursued a hardship discharge from the Army. “I was a mess,” you’ll hear him say. Back home in California, Bond went to work for a paving company, and survived a near-deadly accident when he was pinned between a big rig and a pickup truck.

“I was three-and-a-half inches thick sideways,” he says of the incident that left him with a metal pelvis, hip, and tailbone.

Conscious, but unable to communicate, Bond heard a responding doctor cite a time of death while covering Justin with a sheet. “Three minutes later they heard the end of my prayer from underneath the sheet,” you’ll hear him explain. Appearing to die again on the way to the operating room, Bond instead left doctors mystified by his survival. “It’s not my call when I leave the earth I guess,” he says.

As he recovered from his injuries, the unfinished business he felt from his time in the Army gnawed at him. “I never finished my first tour, I cost the country a million dollars in training and left,” he explains. When terrorists attacked Washington, D.C. and New York City on September 11, 2001, his desire to find a way back into uniform was unquenchable. “Watching those towers fall,” Bond remembers. “It was like a bully came over and punched us in the gut.” Even though he had been told he would never walk again, Bond made his way to the nearest Army recruiter’s office.

“Dude, you’re in a wheelchair,” he remembers being told, with laughs following the recruiter’s incredulous reaction.

Listen to Hometown Heroes to learn how Justin found his way back into the Army, connecting with the 1072nd Transportation Company, a National Guard unit that soon deployed to Iraq. Bond’s job in the Humvees or Palletized Loading Systems (PLS) he rode in was to help protect the convoy with his M249 light machine gun, also known as a “SAW,” for squad automatic weapon. You’ll hear him relate a vivid memory from his first moments on Iraqi soil. A Muslim woman in her 60s approached the Americans, kissed their feet, and shared a message Bond will never forget.

“God bless you, God bless your country, and God bless your God for you coming to die for us,” the woman said.

One of six SAW gunners in a company of 144 men, Bond had just finished three days worth of armed escorts with the third platoon and was settling down to rest when he heard that the second platoon needed a gunner for what appeared to be a dangerous mission. Ignoring his friends’ pleas not to go, an exhausted Bond volunteered to fill in for a fellow gunner who had taken ill. Little did he know that April 9, 2004 would become infamous for the “Good Friday Ambush” that would leave three American soldiers and five civilian contractors dead. Thomas Hamill, a civilian riding in the convoy twenty minutes ahead of Bond’s, would go on to write the book, Escape from Iraq, after being captured that day. Staff Sgt. Matt Maupin was also captured, and later executed in captivity. As you’ll hear him detail, the fact that Bond survived that day is nothing short of miraculous. When his convoy came across the remains of the convoy Hamill and Maupin had been in, the scene was horrifying. Vehicles burning, insurgents visible in the distance scurrying prisoners away. Soon, Bond’s convoy was under attack. He would learn later that he and the twenty other Americans with him were surrounded by approximately 1,000 insurgents. “Pretty fair odds,” you’ll hear him remark. Adrenaline pumping, Bond fired away at the enemy, hoping his convoy would somehow make it through. He didn’t realize he had been hit by enemy fire until his driver pointed it out.

“I looked down and both knees were pulsating blood. I took an AK-47 round through the center of both knees,” Bond explains. “It ricocheted off the engine cover of the truck and went back into my left knee, totally destroying it.”

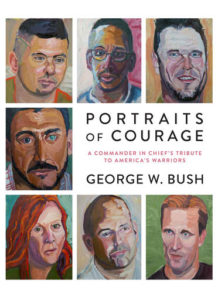

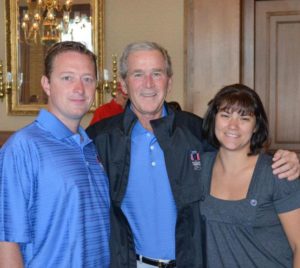

Listen to Hometown Heroes to find out how Bond and every member of that convoy survived, with 17 of the 21 receiving Purple Hearts. You’ll hear how a direct blood transfusion from an Iraqi insurgent prisoner saved his life, and why Justin finally relented to doctors’ advice to amputate his left leg. Bond also explains the most haunting aspects of his service, why he believes “PTSD is a much worse injury than losing a leg,” and explains how he became friends with the man who was his Commander-in-Chief, President George W. Bush. Justin Bond is even featured in the former president’s new book of paintings, Portraits of Courage, with profits from the book going to Bush’s presidential center in Texas for its Military Service Initiative.

Our Heroes’ Dreams originated through Bond’s efforts to respond to fellow wounded veterans who were on the brink of suicide. Through awareness-raising adventures like riding a Segway from California to Florida, Bond has brought attention to the epidemic of suicide in the veteran population, which claims more lives every year than our military has lost in Iraq and Afghanistan combined. You’ll hear him share why he believes giving these warriors a new mission is a crucial component to preventing suicide, and how Our Heroes Dreams has helped more than 400 at-risk veterans.

He also shares his dreams for Our Heroes’ Dreams, which includes acquiring the land for a permanent facility that would welcome veterans and families in crisis, with the goal of helping them heal. “Camp Freedom” would serve veterans of all generations. “Camp Liberty” would become a place of solace for families who lost veterans in combat, or to suicide. “Camp Uniform” would provide a healing retreat for first responders and other civilians who have no access to VA benefits. Our Heroes’ Dreams will need to raise approximately $2 million to bring those dreams to fruition, but driven by that burning desire to quell veteran suicides, Bond believes it will happen.

“I’m not a hero,” he emphasizes. “The heroes are the guys that went over there and never got to come home. They came home to the 21-gun salute.”

Memorial Day is a very difficult day for Justin Bond. He reflects on his fellow soldiers who were killed in Iraq, and how close he came to adding to their number. In his mind, every veteran suicide adds a preventable number to that growing list of tragic wartime casualties. After 37 operations, including his latest to install a revolutionary new prosthetic, and all the life-threatening situations he’s survived, Bond is convinced that his purpose in life is to bring hope and healing to veterans by giving them a new mission. If you would like to support the mission of Our Heroes’ Dreams, or you know a veteran in crisis that could be helped by the program, call 1-844-OHD-VETS or contact the organization online.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply