Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

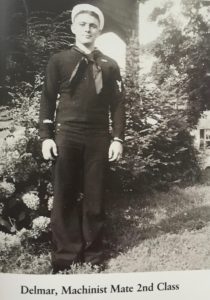

96-year-old Del Schwichtenberg of Carson City, NV appears on episode #526 of Hometown Heroes, airing June 1-3, 2018. Schwictenberg enlisted in the Navy in July, 1940, shortly after graduating (with a class of 18 students) from Oswego (IL) High School.

His parents had been potato farmers in Becker, MN, but a drought cost them their farm and they moved south to Oswego, 35 miles southwest of Chicago, along the Fox River. Del, an only child, built model airplanes and dreamed of flying someday. Working at a local garage for a wage of 12 cents per hour, he saved up to pay for flying lessons at nearby Joliet airport. Two weeks before his 16th birthday, in January 1938, he earned his pilot’s license. Taking night school classes in the hopes of becoming an apprentice mechanic for United Airlines, Del’s ambition was derailed by the advent of the FAA, which eliminated that apprenticeship program. With unemployment at 25%, the Navy presented an attractive option, and the idea of submerged service offered an unexplored frontier.

“I didn’t know anything about submarines, and that’s the reason I chose submarines over aviation,” you’ll hear Del say.

Listen to Hometown Heroes for the hurdles Del had to clear in submarine school in New London, CT, including the different tasks he had to master to qualify for a sub’s crew. Assigned to the SS-06, a World War I-era submarine, he would go out on training runs twice a day, showing new would-be submariners the ropes. On December 7, 1941, Schwictenberg and other sailors at the sub school learned that all their training would be put to use sooner than they expected.

“I was helping the chief wash his car,” says with a chuckle of that fateful Sunday. “All at once the radio started to blare out the news that Pearl Harbor was being attacked.”

Del was forced to deal with tragic loss before he ever headed overseas. Aboard the USS-06 for a training run with two other submarines, he was stunned by the awful realization that one of the subs never resurfaced. 28 men, some of whom he had gotten to know very well during training, would be forever entombed in that mortally damaged boat, 400 feet below the surface. You’ll hear him recall losing a couple nights’ sleep after that, and the unwelcome feeling that tragedy produced for a young sailor. “It was very similar to sinking Japanese ships,” he shares. “You think about the amount of lives that were lost.” That sense of loss is would become a recurring experience throughout five war patrols on the USS Sand Lance (SS-381), operating in the Pacific from 1944-45.

“The submarine force was less than 2% of the Navy,” you’ll hear Schwictenberg explain. “We sank over half the Japanese fleet. We lost 52 submarines out of a possible 249.”

Roughly 3500 men lost their lives on those 52 fallen submarines, which you can read more about in this official Navy report. The US Submarine Veterans, Inc. honors the legacy of those boats by naming local chapters – called “bases” – of that veterans’ group after subs that were lost. Del is a proud member of the Corvina Base in northern Nevada, named for a boat sunk by a Japanese submarine in November, 1943.

Assigned as chief auxiliaryman on the Sand Lance, Del was responsible for damage control, and maintaining and repairing every piece of mechanical equipment on the boat, except for the engines and water distillers. The threat of damage – or death – became an ever present danger, with the submarine experiencing frequent contact with the enemy. He can only recall one instance in which the Sand Lance sank an enemy ship and did not become the target of the depth charge in response. If that brought an unusual sense of relief, it didn’t last long. They soon heard mine cables scraping against the boat’s hull. In all of those instances in which depth charges were detonated, the experience aboard the submarine was unnerving.

“Sometimes you’d look down at your feet and the deck,” you’ll hear him remember. “and you’d be about six inches up off the deck from the movement of the submarine.”

Listen to Hometown Heroes for Schwictenberg’s explanation of how his damage control team stopped a leak that resulted from one depth charge attack, as well as the heroic repair effort that would lead to his being awarded the Bronze Star.

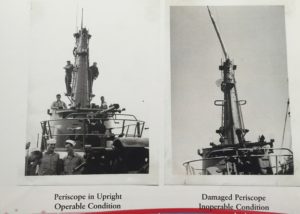

After an engagement with Japanese and Russian ships in the Sea of Okhotzk, the Sand Lance’s attack periscope was damaged by an iceberg. Bent severely, it would not retract. Schwictenberg and the damage control team had to find some way to remedy the situation before the inevitable enemy attacks would doom the ship. Listen to Hometown Heroes for how close a Japanese air attack came to sinking the submarine, and what kind of resilience and improvisation it required to finally restore the boat to operational status. Using a combination of electric drills, cold chisels, and some scrap metal they had snagged on their way out of the U.S., they endured a snowstorm to complete a seemingly impossible job.

“Two days and two nights we worked on that periscope,” you’ll hear him remember. “The hardest way you possibly could do it.”

The citation that accompanied his Bronze Star, signed by Admiral Chester Nimitz, notes his “outstanding performance of duty,” the fact that he endured a snowstorm and the threat of enemy air attack, and commends “his efficiency and his coolness under the most trying conditions.”

“His conduct throughout was an inspiration to all with whom he served,” the citation concludes. “And in keeping with the highest traditions of the naval service.”

You can read more about Del’s journey in this Nevada Appeal article by Ken Beaton, who introduced us to this submariner and his unique story.

After enduring enemy aerial bombs, torpedoes (even 3 days after Japan surrendered), depth charges, and other hazards, Schwictenberg is very thankful to have survived it all.

“I think I’ve had a guardian angel looking after me several times in my lifetime,” you’ll hear him reflect.

In 2012, Del had the privilege of visiting the National World War II Memorial with Honor Flight Nevada. Looking at the “Freedom Wall” of gold stars, representing more than 406,000 Americans who died while serving in World War II, and including those 3,500 of his fellow submariners, left him with one clear sentiment.

“I thought how lucky I was,” he says. “You win some and you lose some. I’m fortunate I’ve won more than I’ve lost.”

If you ever encounter this spirited submarine veteran in Carson City, or perhaps at one of his regular Corvina Base meetings in Reno, please thank him for serving our country.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply