Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

Joe Soldo of Clovis, CA appears on episode #557 of Hometown Heroes, airing January 3-6, 2019. Soldo, who will celebrate his 95th birthday on January 8th, served with the 78th Infantry Division in Europe during World War II and spent more than five months as a prisoner of war.

Croatian was Joe’s first language, born in Pennsylvania to immigrants from what was then known as Yugoslavia. He learned English in school, and a job at the local Texaco station gave the teenager more than just a paycheck. You’ll hear why he loved the uniform, how he met the Andrews Sisters, whose songs like “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” would soon become ubiquitous, and he received some encouragement from his boss that altered his outlook.

“I was going to work in the steel mill like my father,” you’ll hear Joe remember. “No, you can do a lot better than that,” his boss told him. “You can do anything you want, you’re smart enough.”

Soldo studied engineering for a year at Lehigh University before signing up for the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which took him to Boston University. A year later, ASTP was disbanded because of the need for troops. Joe was assigned to the 78th Infantry Division, and in April, 1944 reported for eight weeks of intensive training to prepare for combat. His mother, who had lived through World War I in Europe, was concerned that Joe may suffer the same fate she had witnessed befall so many a quarter-century earlier. Perhaps her persistent prayers played a role in his survival.

“The first day, we were moving forward,” Joe recalls of his introduction to war. “My best buddy, who was a Yale student, got hit in the middle of the forehead and killed as we walked along.”

On December 13, 1944, Joe found himself in the small German town of Kesternich, near the Belgian border. There were all of 112 buildings in the village, but finding a safe shelter proved very difficult in a fierce fight with the enemy. After days of back and forth fighting, Soldo was ordered to a nearby cellar by his captain, who realized their small group of roughly 20 men was outnumbered.

“Pretty soon the gun of a tank went into the window, pointing at us,” Joe recalls. “I thought it was the end, but it wasn’t.”

While another group of 78th Division soldiers was famously rescued from a Kesternich cellar, Joe and the men in that particular cellar were taken prisoner, counted among the more than 1,500 American soldiers who were either killed, captured, or listed as missing in action as a result of that first Battle of Kesternich. The Allies would eventually capture the town six weeks later. By that point, Joe Soldo was already coming to grips with the reality of being a prisoner of war, and had even witnessed the aftermath of one of the Nazis’ most infamous war crimes. His ability to speak multiple languages, specifically his familiarity with German and Russian, made him valuable to his captors, who used him as an interpreter as they marched Joe and more than 100 others through the snow. Roughly 25 miles southwest of Kesternich, the freezing, battered, hungry crew came across a grisly scene.

“I remember marching along and then coming to a field where about 41 American prisoners were shot. They were all dead,” he says of one element of what would become known as the Malmedy Massacre. “The bodies were there.”

It would be more than five months before Soldo would taste freedom again, and he spent the coldest winter Europe had experienced in decades being marched from camp to camp, without the heavy overcoat his captors had taken away from him. At one point, he had to carry, on his back, a fellow prisoner who had suffered frozen feet.

“If I’d have left him back there, they might have shot him,” you’ll hear him say of his friend John Dodson. “Because they were not waiting for stragglers.”

A strapping 180 lbs. at the time of his capture, Joe would drop below 140 by the time he was liberated. Food was so scarce that he once traded his high school class ring for some bread. In the video below, Joe shows us a unique item he received when bartering on a more satiated stomach.

That hand-crafted box, acquired in a trade with a Russian prisoner, is a visual reminder of the many unforgettable things he witnessed while being transported from camp to camp, continuing to serve as an interpreter. Many of those miles were covered on foot, while others came aboard “40 and 8” boxcars meant to house 40 men or eight horses. At one point, there were more than 100 men crammed in one of those train cars when it stopped in a marshaling yard. American planes, unaware that prisoners of war were inside, shot up the train. One prisoner was killed, and the rest had to remain standing around that dead body for more than a day, locked in that car with no room to move. The group passed through multiple prisoner of war camps, and even some concentration camps. The most horrific moments of his entire ordeal came in the two days the group spent at the infamous Auschwitz extermination center in Poland.

“They were taking the corpses and taking the gold teeth out of the corpses,” he says in reference to just one of the gruesome scenes he witnessed in a place he once described as “a peek into Hell.”

Eventually, Joe was taken to Stalag X-B in Sandbostel, Germany, near Bremen. Trading the occasional barn to sleep in for barracks with three-high bunks, he adjusted to life at a large complex that held Russian, British, French, and American prisoners, as well as political prisoners in a portion of the compound that was really a concentration camp. The camp commandant had agreed to hand Stalag X-B over to its prisoners on April 21, 1945. Two of the prisoners left the camp and found a British unit nearby. On April 29, those troops officially liberated the camp. The chaos, uncertainty, and potential for clashes erupting led Joe to seek a unique hiding place in the kitchen.

“I opened it up, it’s empty, I went in,” he says of the large soup pot he hid in for close to 4 hours. “Until I heard English voices.”

A Scottish regiment, complete with bagpipers, had taken over, and after 134 days in captivity, Joe Soldo was once again a free man. He says he spent many of those days praying that he would one day have a family of his own, and he knew his parents and siblings back home in the states were praying for him too. When he returned to Pennsylvania, his mother grabbed his legs, sweeping her hands up and down to make sure they were still intact. He had seen and experienced things no 21-year-old should, but indeed, he returned with his body intact.

“Survival is an instinct,” you’ll hear Joe say. “I always had faith that I’d get out.”

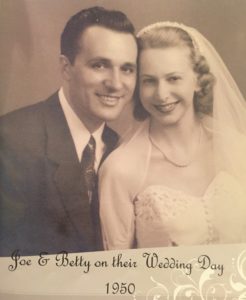

He worked his way through Notre Dame by cutting hair, later earning a graduate degree from the prestigious Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. He met and married his wife Betty, they raised three children, and enjoyed 68 years of marriage before her passing in July, 2018. Just three months earlier, she got to welcome Joe home from his journey to Washington, D.C. with Central Valley Honor Flight. You’ll hear Joe speak about his visit to the National World War II Memorial, where he was met by his congressman Devin Nunes, who also arranged for Joe to receive his long overdue Prisoner of War medal.

You’ll hear briefly from one of Joe’s sons, Andy, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, who understands he and his siblings would not exist if his father hadn’t survived those five harrowing months as a prisoner of war.

“Survival isn’t always by choice, it isn’t by willpower, it isn’t by might,” you’ll hear Andy opine. “It’s really by the blessing of God.”

If you ever enjoy the blessing of meeting Joe Soldo, make sure to thank him for his service to our country, and ask him if he has his harmonica, because you might just be treated to a melody like the one in the video below.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply