*IN MEMORIAM*

Joe Garabedian passed away November 1, 2020 at the age of 96. Click here to read his obituary from the Fresno Bee.

Use controls above or click here to open this Hometown Heroes podcast in a new window

96-year-old Joe Garabedian of Fresno, CA appears on episode #642 of Hometown Heroes, airing August 20-24, 2020. Joe was wounded by a sniper’s bullet while serving with the 96th Infantry Division during World War II, and spent the next year without the use of his left arm.

His injuries did not stop him from launching Valley Welding & Machine Works with his two older brothers in 1946. Agricultural clients around the world rely on VWM to design and fabricate custom equipment, primarily for the dried fruit and nut industries. When Joe makes his weekly sojourn to “the shop,” his three children and three of his grandchildren are among the employees he visits. None of them would exist if his life had not been spared on October 28, 1944.

The ninth of ten children growing up on a 20-acre ranch in Lone Star, CA, which you’ll hear him refer to as an “oasis,” Joe helped tend to cows, horses, sheep, goats, and chickens. You’ll hear how those animals, and his mother’s garden, covering a full acre, helped sustain the family of twelve through the Great Depression, and also how Joe went about tricking his father in order to play football for Fowler High School. Joe played right guard and right tackle, making memories against rival schools like Sanger and Selma. In the middle of his senior year, he was on a tractor on the ranch in Lone Star when he received word of Imperial Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

“It was very hard for me to believe because our neighbors were Japanese,” you’ll hear Joe recall. “We were friendly with all of the Japanese here. We went to school with a bunch of them. It was just unbelievable.”

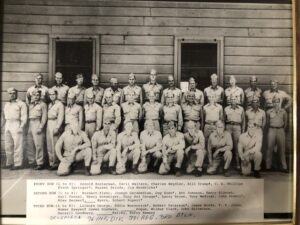

Americans of Japanese ancestry soon had their movements restricted. When his neighbors, the Yamamotos, weren’t allowed to drive into downtown Fresno to take their strawberries to market, Joe volunteered to do it for them. He also visited them in the Fresno Assembly Center, one of the temporary holding facilities where Japanese-American families were taken before being forced into internment camps. Joe had started working for Commercial Manufacturing the year before, and he enjoyed welding so much that he thought he might work there forever. Since he was still helping on the ranch as well, he was told by the family doctor that he could qualify for an agricultural deferment and avoid military service in World War II. Color blindness derailed his attempt to enlist in the Navy, so Joe was drafted into the Army in February, 1944. The need for soldiers was so great that Joe bypassed boot camp, and was sent directly to Camp White near Medford Oregon, to join the 96th Infantry Division.

The 20-year-old was trained as a rifleman, then with a .30 caliber water cooled machine gun. In July, 1944, the division moved to Camp San Luis Obispo, where Joe and his fellow “Deadeyes” practiced amphibious landings in Morro Bay, CA. After further training in Hawaii, they embarked on a forty-day journey to the Philippines. October 20, 1944, the day General Douglas MacArthur made good on his “I shall return” pledge by wading ashore on the island of Leyte, was the same day Joe Garabedian arrived at Leyte for his first taste of combat.

“We had to set our machine guns, eight machine guns, two feet off the ground so that they would shoot over our infantry,” you’ll hear Joe explain. “When the Japanese would come with their banzai, like 200 at a time, we had our machine guns all set ahead of time.”

Listen to Hometown Heroes for Garabedian’s detailed explanation of how their machine guns operated, what the members of his squad had to master, and what their instructions were for how to approach firing the weapon in combat. By October 28, 1944, Joe had spent eight nights trying to sleep in foxholes that would be inevitably filled with water. He had picked up a pair of binoculars that an officer had discarded, and he was looking through them when he was struck by enemy fire.

“Zing! Right through my shoulder,” you’ll hear him say of the sniper’s bullet that tore through the brachial plexus in his left shoulder and exited near the base of his spinal cord. “I got up, I started running, I had run about ten feet, the blood is squirting out. I’m hollering, ‘Medics, Medics!’ and I fell down.”

After bandaging his wounds and administering morphine, the medics pulled Garabedian onto a stretcher. As gunfire continued to reverberate through the area, another wounded soldier named Tony Medziak grabbed a hold of Joe’s stretcher. With one hand, Medziak pulled Garabedian under the cover of some nearby brush, where they remained until the firefight subsided about thirty minutes later.

By that evening, a jeep arrived to evacuate Joe and two other wounded men to a field hospital. You’ll hear Joe explain why he didn’t have his dog tags, and why a replacement paper tag ended up mangled and bloodied. He was soon transported via hospital ship to Hollandia, New Guinea, where he would receive further medical attention.

Joe had been told the average machine gunner lasted three minutes in combat. He had made it through eight days, but now wasn’t sure if he would be able to keep his left arm, let alone ever use it again. You’ll hear Joe relate that the bullet wound felt like a “bee sting,” and while it ripped through muscle, tendon, and nerve tissue, it did not strike any bones, exiting less than an inch from the spinal column in the middle of his back.

“I’d have been paralyzed,” he says of the fraction of an inch that separated him from a spinal injury. “That shakes me. In fact it shakes the doctors when they see it, to be that close to the spine.”

Garabedian would spend the next year in hospitals, and couldn’t use his left arm for more than a year. One day, he felt a twitch in his bicep that told him the some of the muscles were starting to respond again, and little by little he regained most of the strength in that left arm.

Discharged from the Army in November, 1945, one of the biggest decisions in Joe’s life came in 1946. His $2,000 investment was matched by both of his older brothers, Mike and Charlie, as they launched Valley Welding & Machine Works. Joe had learned how to weld in high school, and soon he was figuring out how to operate a lathe. When bodybuilding champion Harold Zinkin envisioned the Universal Gym, the world’s first four-station weight machine, it was Valley Welding & Machine Works who turned that idea into reality. Much of the brothers’ early work involved designing and fabricating machines for the raisin industry. Over all the decades since then, the business has expanded to serve other dried fruit sectors as well as the nut business, producing custom equipment for agricultural clients all over the world.

“It’s hard to believe that three high school graduates would start a business like that,” he says of the company that continues to grow under the leadership of Joe’s son, Mike. “Customers like this. They like the way we did business.”

Joe makes it a point to visit the shop at least once a week, and while the business may be his “baby,” it’s also a good way to see his three children and three grandchildren who work there. Watch the video below for more from Joe and Mike about the legacy that Valley Welding & Machine Works represents for the Garabedian family.

—Paul Loeffler

Leave a Reply